Between 6 River Systems and CarGurus, a very significant amount of my time over the past five years has been dedicated to data platform automation, reducing cross-team friction, and improving data quality.

Schemas have played a critical role in the process; this post outlines the why and the how. But before diving straight into the role of schemas (er... contracts) let's talk data platforms.

Components of a Good Data Platform

Instrumentation and Integration

This one goes without saying. If data is not being emitted from source systems you won't have any data to play with.

If you don't have any data the rest of this post will not provide value. You also won't be able to complain about the price of Snowflake and might feel left out.

Instrumentation is pretty important. It's also a pretty huge PITA to wrangle, which is why tracking plans became a thing.

The pipeline

Pipelines are either batch or streaming. There's a holy war between the two religions, but similar concepts apply to both.

Pipelines collect data and put it somewhere. Sometimes they mutate said data. That's really it.

The best pipelines:

- Move data reliably.

- Annotate payloads with metadata such as provenance,

collected_attimestamps, fingerprints, etc. - Generate stats to provide the operator with feedback.

- Validate and bifurcate payloads, if you're lucky.

- Know about and act on payload sensitivities - obfuscate, hash, tokenize, redact, redirect, etc.

- Minimize moving pieces.

- Don't spend all the CEO's 💸💸💸 so they can afford that house in the Bahamas.

Storage and access

Data has to be stored somewhere- preferably somewhere accessible.

Storage/access systems range from a wee little Postgres database, to Snowflake, to a data lake filled with Parquet fish and the Loch Ness Trino monster.

Data Discovery

As things scale, pipelines/databases/data models often turn into something the James Webb and dbt can't stitch back together.

Data discoverability is super important when organizations are fragmented, or when you're new to the company, or when you forget stuff as I often do.

Observability, Monitoring, and Alerting

Last, definitely not least, and unfortunately-rare... tools that tell the operator if things are broken.

These could be devops-y tools like Prometheus/Alertmanager/Grafana, pay-to-play tools like data quality/reliability platforms, or something dead-simple like load metadata tables and freshness checks.

Design Goals of a Good Data Platform

Comply with rules

While maybe not the case within the US (for us Non-Californians), data regulation and compliance is kind of a big deal. If you don't comply, good luck.

Compliance is becoming less of a goal and more of a requirement.

Minimize bad data

Bad data is expensive. It's expensive to move, it's expensive to store, it's expensive to keep track of, and it's expensive to work around. Not knowing data is bad is even more expensive.

Maximize knowledge of what the system is doing

Good things come from a knowledge of what a system is doing and when it is doing it.

Only after measurement can you optimize cost.

Only after timing can you make things faster.

And only after seeing a system end-to-end can you cut out unnecessary intermediaries.

Minimize friction for all parties involved

Data platforms should be a good experience for everyone. Which includes many more parties than just analytics engineers or analysts.

Parties who are critical to success include:

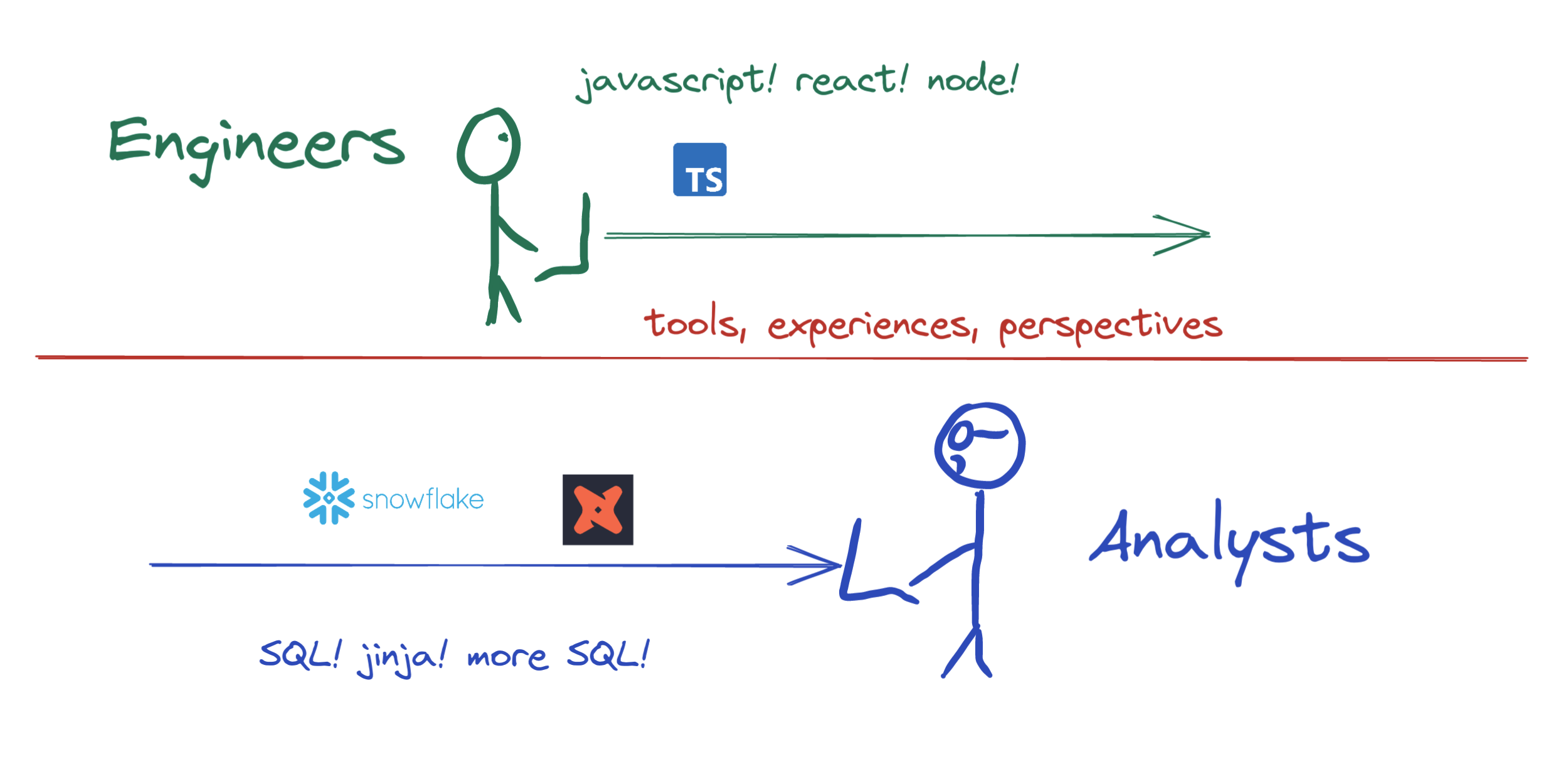

- The frontend engineers, who work with Javascript/Typescript and any number of frameworks

- The backend engineers, who work with Python, Node, Java, Go, C++

- The native/app engineers, who work with something like Swift, Flutter, React Native

- The devops people, who like when they can write less Terraform.

- The SRE people, who like when they can see what's going on without asking you. Because you'll probably be asleep when they try.

- The data engineers, who are usually on the hook when data goes bad.

- The analytics engineers, who like when

user_idmeansuser_id. - The analysts, who like when they can push value back to product engineers.

- The financefolk, who will come after you when costs exponentially increase.

- The businessfolk, who will also come after you when costs exponentially increase.

While data mandates and a new breed of data-oriented law might sound lovely (or not), these mechanisms only benefit a couple of the above parties. Mandates don't work. Telling other people to have more responsibility, so you can have less, also doesn't work.

Want to get buy-in? Minimize friction. Want to increase adoption? Automate others' toil. Want sustainable systems? Reduce cognitive load.

Which brings us back to schematizing stuff.

The Contract-Powered Platform

I'm going to go out on a limb and just say it -> schemas are the nucleus of sustainable data platforms.

Schematizing data upfront is often initially discarded and seen as unnecessary overhead or a productivity drain. The idea is nixed in favor of the eventual chaos arbitrary json creates. But who cares about our hypothetical future selves - it's our current selves that matter. Let's dig in for the sake of science.

Schemas empower the "producer" <-> "consumer" relationship

Let's think about the two ends of data systems for a second.

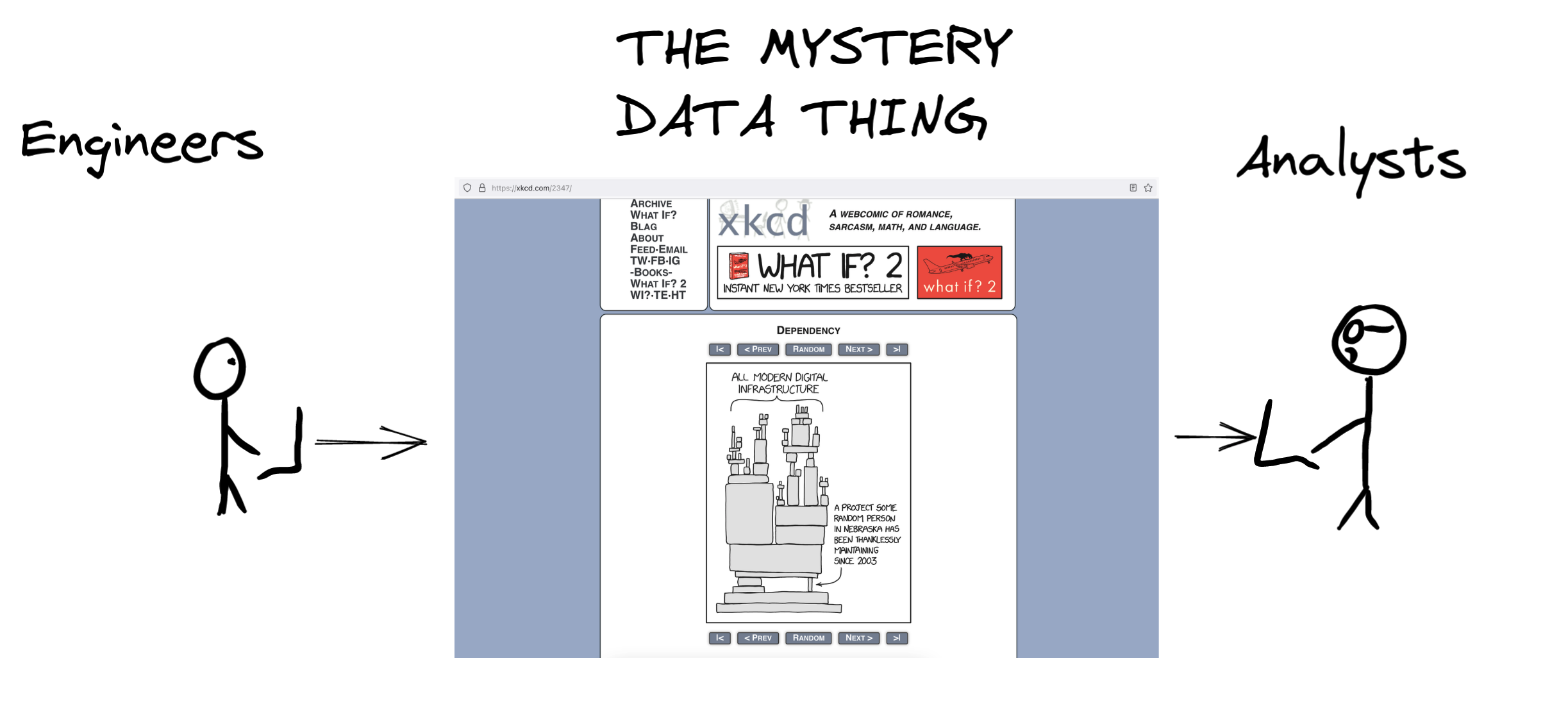

Engineers exist at the source, product analysts typically exist at the "destination", and a black box lies between:

But when the mystery data thing is removed, the engineer <-> analyst dynamic actually looks more like this:

This working dynamic is pretty terrible for productivity. The two parties communicate, sometimes. There's a ton of friction and neither party is to blame. Data engineers and managers are asked to join the conversation, and implicit "contracts" are established in a Google doc that everyone will lose track of.

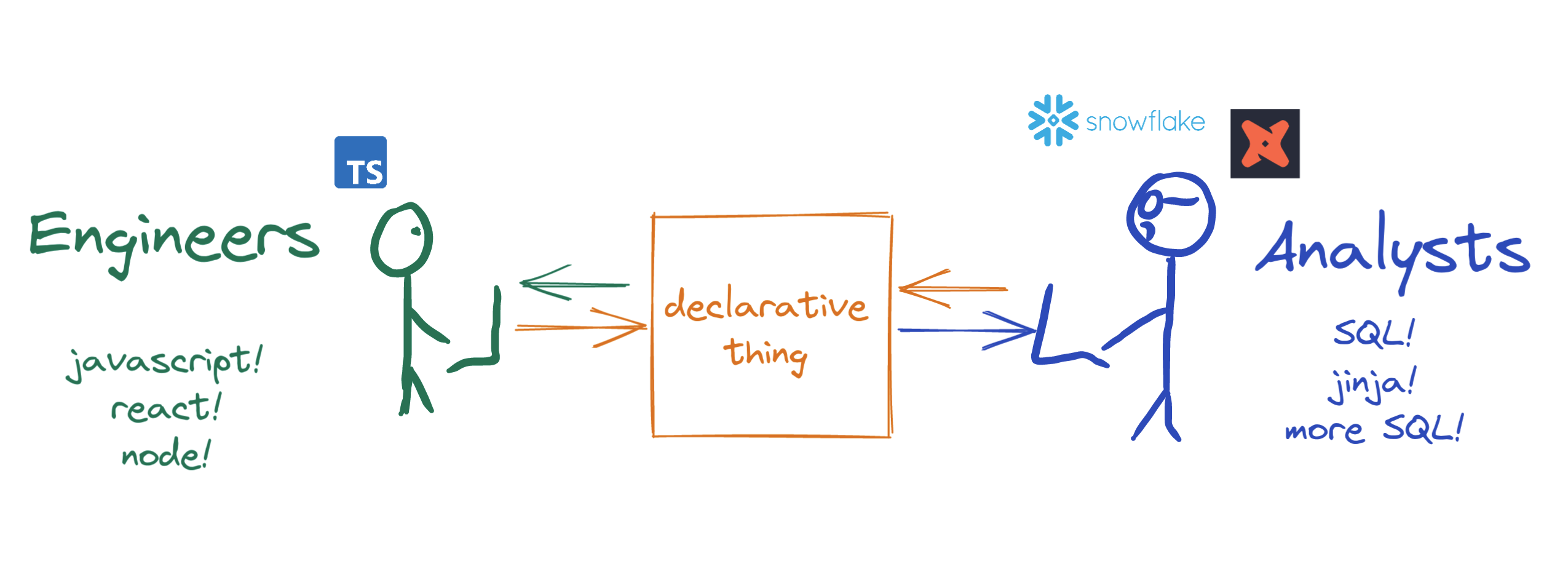

(Human-readable) schemas turn this dynamic into something that looks more like the following:

Both parties contribute to a schema with consistent verbiage, which is then leveraged to generate the equivalent data structure in their language of choice.

Today's data workflows look very similar to how software engineering looked prior to Github announcing Pull Requests in 2008. They work, but aren't ideal.

Schemas are data discovery

In LinkedIn's popular metadata architectures explained, pull-based metadata extraction is outlined as "an ok start". Push-based metadata is "ideal".

Schematizing data upfront means data discovery and documentation writes itself. Data assets are discoverable as soon as schemas are deployed - before the data actually starts flowing.

Schematization mechanisms like JSON Schema also get pretty meta, so it's easy to add annotation such as:

- "These properties contain PII"

- "These properties should be tokenized"

- "X person on Y team owns this schema"

- "This is version

1.4. Here's how this data has evolved from1.0."

This class of metadata is a CISO's dream.

Schemas power data validation in transit

Comparing a payload to "what it was supposed to be" and annotating it with a simple 👍👎 is extremely valuable. Schemas are the "what it was supposed to be".

Schemas help stop bad instrumentation from being implemented in the first place

Another +1 (for engineers) is the fact schemas help prevent bad tracking from getting deployed in the first place.

Language-specific data structures can be generated from schemas. Which means intellisense or the compiler complains during development if required props are missing, or if one is a string and should be a bool. And then the code blows up again at compile time if the bug is still there.

Nobody likes being the person who causes the release train to halt. Or being the person who caused the rollback because a prop was missing. Especially when it's "just for analytics".

Merging to main only after instrumentation is 👍👍 is the ideal workflow. It saves rollbacks. It avoids the human friction of going to the data team... again, to have them explain their mandated "contract".

And it's just good engineering.

Schemas improve code quality

This might be a stretch. Or maybe not.

Have you tried forcing an engineer who loves Typescript to use Any, while simultaneously mandating payloads have propA, propB, and propC. And propC must be a bool?

Or tried forcing a golang-oriented engineer to use a map[string]interface{}, but told them the payload must have specific keys?

I have. And it was pretty silly. And a couple quick Google searches highlight Don't Use Any. Use map[string]interface{} sparingly. Lint rules will not-so-nicely tell you to pound sand.

Schemas are centralized verbiage from which to generate language-specific data structures. Tools like Quicktype, Typebox, and jsonschema-to-typescript make this a reality. The same can be said about JTD and Protocol Buffers.

Schemas power automation

Schemas make data engineering quality of life significantly better. Destination tables can be automatically created and migrated as schemas evolve. Kafka topics and Pub/Sub streams can be automatically provisioned using the schema namespace. A single stream can be fanned out to a dynamically-partitioned data lake. And a whole lot more.

Schemas as observability

Calculating namespace-level statistics and splicing them into observability tools is the natural next step.

Stakeholder FAQ's (long before actual analytics) commonly look like:

- "I just implemented tracking. Is the data flowing?"

- "When was some.event.v1 first deployed?"

- "Is some.event.v1 still flowing?"

- "Are we seeing any bad events after most recent deploy?"

- "How much data are we processing for schema x.y.z?"

- "I just changed some javascript. Am I still emitting one event or has it become ten?"

- "What team should I go ask about a.b.c?"

- "How does this event get generated again?"

When the name/namespace of a schema is present with each payload, and payloads are shipped to tools like Datadog, people can self-service answers to these questions.

When the name/namespace of a schema is present with each payload, and the payloads are loaded into Snowflake, people can self-service answers to these questions.

Self-service, low-cognitive-load systems minimize friction for everyone.

Schemas power compliance-oriented requirements

(Actually) adhering to data privacy-oriented regulation requires a rethink of pretty much all data processing systems. The place to tokenize, redact, or hash personal information is not at the end of the data pipeline. It is at the start. Otherwise you'll have sensitive data lying all over S3 in cleartext or flying through Kafka with no auth, and zero clue how to actually find or mitigate it.

Schemas are the foundation of higher-order data models

It is pretty easy to turn a schema into a dbt source so analytics engineers can reliably build upon a well-defined, trustworthy foundation.

If the foundation is not strong the analytics engineering team will spend all their time building "layer 1 base models" to santize inputs. In non-professional settings this would be called Whack A Mole.

Schemas are the foundation of data products

Similar to data modeling benefits, schemas allow data products to be built on a solid foundation. But there's more that can be done on top of that foundation!

Automatically-generated endpoints, GraphQL queries, and API docs? Can do. Tools like Quicktype, Transform, and Apollo immediately come to mind. As does a blog post from the folks at Wundergraph.

"Schemas at the center" is a pattern engineers are already comfortable with. OpenAPI is simply a declarative schema between API's<->frontends after all.

The Contract-Powered Workflow

This is the workflow I've settled on after years of flipping levers and seeing what works (and what doesn't). Mandates don't work. Making analytics teams happy at the expense of poor application code going into production doesn't work. Knowing instrumentation is bad only after it is deployed works-ish, but just barely. Would not recommend.

Draft, iterate on, and deploy a schema.

The neat thing about schema-first workflows is non-engineer stakeholders can write the first draft. You don't have to be a Typescript guru to get the process going, though engineering counterparts will need to be involved eventually.

The more work that can be front-loaded to non-engineers the better. Everyone's time is valuable and schemas allow everyone to proactively contribute to the process. It sucks when useful contributions are discarded because they are "not in a usable format" (cough, Gdocs). Schemas are usable formats.

Bring tracking libraries and systems up to parity.

The second a new schema or updated version has been published, automation kicks in and (at minimum):

- Builds and deploys new tracking SDK's for engineering teams

- Pushes schema metadata ∆ to data discovery tools

- Ensures infrastructure dependencies (Kafka topics, database tables, etc)

- Pushes the schema to the appropriate place for pipeline-level validation

- Creates dbt sources for the analytics engineers

Implement tracking.

Once systems are ready to accept the new instrumentation, engineers implement it into a codebase. It doesn't matter if this is frontend code, backend code, cli's, infrastructure tooling, etc - the process is the same.

Getting dependencies squared away takes a matter of seconds. By the time engineers are ready to implement the new tracking, the entire system is ready to go.

A question I've heard over and over from engineers is "how do I know these payloads are making it to where they need to be?" This question is best answered with "go check Datadog/Graylog/Whatever". And followed up with, "or you could also go check Snowflake for a table of the same name".

The faster engineers have feedback the better.

Deploy.

And lastly - making tracking part of the codebase. A huge pain point of analytics-oriented instrumentation is the fact it's often identified as "bad" after being pushed into prod. This is not awesome, and it greatly contributes to the upstream "we'll just throw arbitrary json down the line" concensus. Everyone knows this is not ideal, but it's definitely better than rolling back every-other deploy due to analytics bugs.

With contract-powered workflows the following prereqs are taken care of before instrumentation rolls out, not after:

- Implementers and stakeholders talk to each other using shared verbiage.

- Versioned, language-specific data structures are generated like all other code dependencies.

- Metadata is pushed to discovery tools.

- The pipeline is primed to accept incoming payloads and mark them as "good" or "bad".

- Observability tools are ready to go for instantaneous feedback in development and production.

- Downstream analytics/modeling entrypoints (like dbt sources) are in place and can be immediately used.

The Schema-Powered Future

If it's not obvious by now, schemas are awesome.

These workflows have significantly improved my work life, I know they've improved my colleagues', and it's probably just a matter of time before they improve yours too.

The fun part is it feels like this ecosystem is just getting started, and there are so many additional implications for the better. It's not a new or original concept by any means. But as data management capabililities at Non-Google companies progress, it will be a consistent solution for consistent pain.

Some other reading if you want to dive in:

- Data Wrangling at Slack

- Jitney at AirBnb

- Pegasus at LinkedIn

- Dragon at Uber

- Building Scalable Real Time Event Processing with Kafka and Flink at Doordash

- Data Mesh at Netflix

- Building a Real-time Buyer Signal Data Pipeline for Shopify Inbox

You could also:

- Tune in for Getting jiggy with JSON Schema at dbt Coalesce or join the conversation on Twitter.

As closing context from a Shopify perspective, 9800+ schemas and 1800+ contributors (many of whom are not engineers) is a huge feat. As is deploying hundreds of schema-generated instrumentation blocks to thousands of robots around the world. The model works.

Here's to our schema-powered future 🥂.